The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil praised efforts by stakeholders and local governments in Southeast Asia to implement the world’s first jurisdictional commitments on sustainable palm oil production on Monday, calling the measures an inspiration for other palm oil producing nations.

Regional governments in the Malaysian state of Sabah and the Indonesian province of Central Kalimantan are currently working with key stakeholders to rollout a sweeping sustainable palm oil initiative. Under the pledge, all palm oil produced in Sabah and sub-jurisdictions of Central Kalimantan would have to meet RSPO certification standards in a move that would catalyze everyone, from large multinational plantation owners to smallholders, into the approach. RSPO Secretary General Darrel Webber called the move an important step forward for the future of the industry.

“From the RSPO’s perspective, we want to achieve maximal impact and certifying farm-by-farm is useful, it is impactful, but we want to make an impact in more than just a localized area,” Webber said. “Now that we have a few jurisdictions in the region on pilot programs, we hope that it can inspire more regions to do it and hopefully, bad practices that were connected to the industry will be a thing of the past.”

Sabah’s palm oil sector would go 100 percent sustainable by 2025 under the proposed commitment. The Central Kalimantan government is committed to a plan of their own, signing the declaration of “Central Kalimantan’s Pathway to Low-Emission Rural Development” at last June’s Governor’s Climate and Forest Task Force meeting in Barcelona, Spain.

Officials in Africa, Latin America and other Indonesian provinces are eyeing similar commitments. Together, these agreements could represent a tidal change for the palm oil industry, ushering in a future where sustainable practices set the standard.

What is the Jurisdictional Approach?

The approach is a change from previous efforts to establish wider commitments to sustainable practices in the palm oil sector. In the past, individual companies and plantations would enter the RSPO’s certification program, agreeing to undergo RSPO audits of their entire supply chain. In order to meet accreditation standards, the palm oil company has to operate in accordance with the RSPO’s principles and criteria, including presenting proof that no high-conservation value forests were cleared to make room for plantation land and verifying that the the land itself was freely owned by the company.

While Webber notes that past efforts to enroll individual stakeholders in the RSPO certification program has worked, smallholders have struggled to meet the requirements. Small-scale farmers have historically struggled to enter the RSPO due, in no small part, to a shortage of capacity necessary to switch to sustainable practices. It’s been a serious hurdle to promoting a wider adoption of RSPO standards in palm oil producing countries. As much as 40 percent of the global CPO stock comes from smallholders in the developing world and in places like Sabah, the inclusion of smallholders is vital to the state’s sustainability ambitions.

That’s why the jurisdictional approach is being heralded as such a positive step forward. When a local government agrees to RSPO certification guidelines, everyone, from large multinational plantation owners to the tiniest smallholders, has to enter the program.

According to Webber, jurisdictional approach will allow the local stakeholders to work with regional governments to improve the welfare of small-scale farmers while curbing the use of environmentally destructive practices like slash-and-burn clearing and ironing out supply chain inefficiencies.

The approach not only presents palm oil-rich nations with an environmentally friendly alternative to damaging practices, but it also offers similarly minded governments a valuable roadmap toward change.

Why is the jurisdictional approach important?

Central Kalimantan is home to millions of hectares of palm oil plantations and is in the heart of one of Indonesia’s two CPO producing regions. Plantations and mills in Sabah produce 12 percent of the world’s palm oil, but the region’s large number of small, privately operated plantations have made it difficult to effect widespread change by approaching individual palm oil producers.

And the effects of years of unsustainable practices, along with illegal logging and the rapid expansion of plantation land, have become startlingly clear. Indonesia is currently struggling to control brush fires that are covering the region in acrid haze. Encroachment remains a concern in the rainforests spread throughout the island of Borneo. The island’s forests are home to an astounding array of animals, plants and insects, making it one of the most biodiverse places in the world.

Now, Sabah officials hope statewide RSPO certification will not only curb destructive practices, but will help local growers sell their product at a premium on the global markets. Environmentally conscious consumers are increasingly concerned with the impact of their purchases, which could make Sabah-produced palm oil an attractive commodity for foreign buyers.

“We know that the world is wanting more and more things out of commodities, apart from the commodity itself, they want to know the sustainability aspects of the commodity,” Webber explained. “So farmers entering this will learn how to future-proof this commodity and protect their income streams by allowing them continued access to all premium markets, including the more sophisticated ones.”

Keep reading

RSPO Board of Governors Endorses Proposal to Form Executive Committee for Operational Oversight

Book Your Slot for the Additional prisma Clinic Session at RT2025

Advancing Jurisdictional Certification in Sabah: Strengthening Collaboration Between RSPO, UNDP, and Jurisdictional Approach System for Palm Oil (JASPO)

Call for Expression of Interest: Independent Investigation of a Complaint

Leading Labels: RSPO Among Top Sustainability Labels in Dutch Market

The 21st International Oil Palm Conference Successfully Took Place in Cartagena, Colombia

Top Performers of the 2025 Shared Responsibility Scorecard

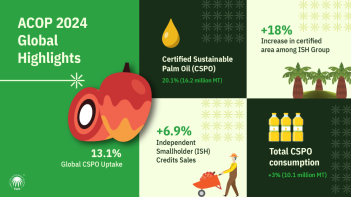

ACOP 2024: RSPO Market Trends Resilient Despite Global Challenges