by: Edem Asimadu

RSPO Smallholder Manager (Africa) Edem Asimadu shares her insights on her field visits to farmer cooperatives in Côte d’Ivoire, with a personal mission to understand the cooperative organisation system that the country is known for.

After ten days on the road, I had travelled across the South of Côte d’Ivoire, meeting with five farmer cooperatives and engaging independent smallholders. The mission was clear – meet with the groups, interview them about their organisation, modus operandi and initiatives, and then profile them for the RSPO Smallholder Engagement Platform (RSEP), our platform designed to facilitate direct engagement between smallholders, partners, and stakeholders. In addition to this primary goal however, I had one personal mission – to understand how the system of cooperative organisation that Côte d’Ivoire is distinguished for translates to the individual smallholder in the village of Déhoulinké in Iboké.

I had one personal mission – to understand how the system of cooperative organisation that Côte d’Ivoire is distinguished for translates to the individual smallholder in the village of Déhoulinké in Iboké.

Cooperatives in the francophone countries of West and Central Africa are required to be organised and operate in line with the OHADA Law (Organisation for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa). Effectively, these cooperatives operate within a legal framework that ensures that their activities are formalised and legally recognised. In Côte d’Ivoire, the national agency responsible for agricultural research and advisory services (FIRCA) leverages the cooperative structure for the implementation of extension services.

At each cooperative, there are extension officers assigned to the different zones. These officers submit monthly reports to their section supervisor, who consolidates and submits to the Director of the cooperative. The Director is then responsible for submitting a quarterly report to FIRCA, the national Association and the Municipality. I noted with intrigue, an elaborate and efficient system of data management, even if characteristically hierarchical.

Oil palm, snappers and rubber: Dauda’s farm

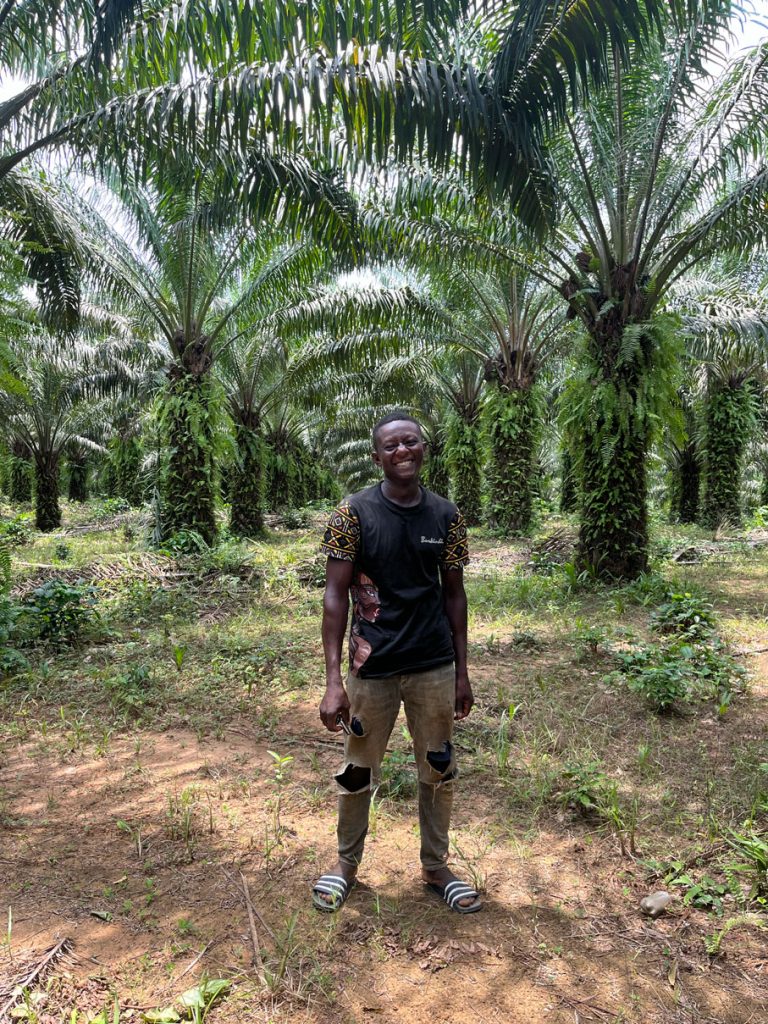

In Irobo, we visited smallholder Dauda’s plantation, an eight-hectare plot of oil palm. We were welcomed under the shade of a bamboo tree. I joined the other officers to marvel at Dauda’s fish farm – four dug-out ponds of red and black snappers – a commonly eaten fish in the country and one I had enjoyed a few times during my visits. As we sat to start the interview, his assigned extension officer flipped through his pocket-sized notebook and confirmed the size of his plantation and went on to mention the different years of planting. The development of the plantation had happened in phases, from 2010 to 2019. I turned to the extension officer and asked, “Were you here when the planting was done?”. As he pondered upon my question, I added, “I’m just wondering how you have that data.” Everyone chuckled as they explained that the extension programme kept a comprehensive database of information related to each farmer. Impressed would be an understatement. I turned my attention back to the farmer and asked some additional questions about the management of his plantation, access to labour, record keeping and access to markets. I was skirting what I recognised could be a sensitive question, but which I had been asking throughout my trip – “Do you own the land?”.

So far, this question had revealed a mix of answers, representing the multiple land tenancy systems being practised across the oil palm growing areas of Côte d’Ivoire and many other producing countries. In this case, the farmer pays monthly rent (per hectare) to the landowner based on a signed agreement. Surprisingly however, there was no defined timeline to the agreement – something I was told was commonplace. Indeed, these agreements are often passed on from one generation to the next. The existence of a signed contract was a pleasant surprise since my discussions hitherto had confirmed the unwillingness of landowners and even community leaders to sign documents of use rights, with fear that they could be misinterpreted as ownership rights.

Shortly afterwards, we arrived at the farm of another farmer, Alhassan. Driving through rubber plantations on roads that were far from accessible by most vehicles, I contemplated the challenging access to smallholder plantations. While the cost of road maintenance is calibrated into the calculation on the national minimum price for FFB, the available budget is often insufficient to maintain all roads. The resulting impact on the transport of harvested FFB and quality of fruits delivered to the mills was undeniable. As we sat on wooden benches to wait for the farmer, I took a photo of the extension officers who had joined the visit and noted happily that the plantation was very well maintained. “This is a farmer field school” they confirmed just as a young looking Alhassan arrived on his motorbike. Farmer Field School is a participatory group-based approach, often adopted for training across various agricultural value chains.

Alhassan and his extension officer confirmed that we were sitting in a 5.3ha sized plantation, belonging to the landowner but fully maintained by the farmer (Alhassan). The latter is responsible for all costs and farm maintenance work, except the cost of fertilisers, which is provided by the landowner. Proceeds from the plantation are shared 50/50 between landowner and farmer. In addition, the farmer also had 2.9 hectares, that he was fully responsible for and for which he kept 100% of proceeds.

I asked once again if there was a written agreement and, in this case, there was none. In fact Alhassan confirmed the plantation and associated terms of engagement had been between the landowner and his father. He had taken over fully when his father became too old to continue the work. I looked on as the extension officers once again reiterated to him the merits of a signed agreement. In our discussion around the cost of farm maintenance and labour services, Alhassan mentioned that his labour costs were relatively lower because he was part of a group of farmers referred to locally as “group d’entrain” where they take turns working on one another’s plantations. The practice is relatively common among smallholder farmers and is not only effective for cost-cutting, but also ensures implementation of Best Management Practices since the group would typically have received the same training.

It was evident that Côte d’Ivoire has one of the most well-developed farmer management systems among the producing countries, giving it a strong base for farmer organisation and support. Specific to certification, the existing system provides the requisite framework for strengthening the cooperative and establishing a comprehensive internal control system, two key aspects of requirements for certification under the RSPO Independent Smallholder (ISH) Standard. Nevertheless, the multiple systems of land tenancy and the suspicion around documenting land use rights will need to be critically addressed, both in line with compliance to the RSPO ISH Standard as with emergent non-deforestation regulations such as the EUDR.

About the author: Edem Asimadu is the RSPO Smallholder Manager (Africa). To get in touch, write her at: [email protected].

Keep reading

Access into prisma

Updated Trace Function in prisma

Call for Expression of Interest: Independent Investigation of a Complaint

Latin American Smallholders, Key Global Brands Gather in Peruvian Amazon to Advance Sustainable Palm Oil

RSPO Forum for Members and Certification Bodies 2025: Strengthening Capacities and Building Bridges with RSPO Members

From Violence to Prosperity: Cultivating Sustainable Palm Oil in San Pablo, Colombia

Palmas de Tumaco: Enduring, Trusting, and Transforming in Colombia’s Pacific Coast

Carry Over Credits for Certified Independent Smallholder Groups